2 Domestication of Farm Animals

This

chapter

contains lots of quantitative data - such as carcass weights and

dressing percentages. They give you an idea of the sizes

involved. It is worth remembering the approximations but not the

details. The details change with different sources.

2.1 Origins of beef

Beef - more than one species. In the

developed countries,

beef is mostly produced from cattle of the genus Bos. However, there are several other genera

which will interbreed with Bos to produce fertile, beefy

offspring: Bison; Poephagus,

the yak; Bibos, the

gaurs; Bubalus, the Indian buffalo; Sunda; and Syncerus,

the African buffalo.

In Canada, our interest is in the main evolutionary

steps from Bos primigenius (wild

cattle of ancient Europe, now extinct), to Bos longifrons (the first

domesticated cattle leaving fossils found in archaeological

excavations), to Bos taurus

(modern cattle).

In the tropics, there may have been another sequence, from Bos nomadicus (wild

ancestors) to Bos

indicus (current heat-resistant cattle). B.

indicus,

which may have been derived from B. nomadicus, is now

recognized by the

following features: a prominent shoulder hump of muscle supported by

dorsal

spines of the vertebrae, a long face with drooping ears, upright horns,

small

brow ridges, a prominent dewlap, slender legs, and uniform colouration

(white,

grey or black).

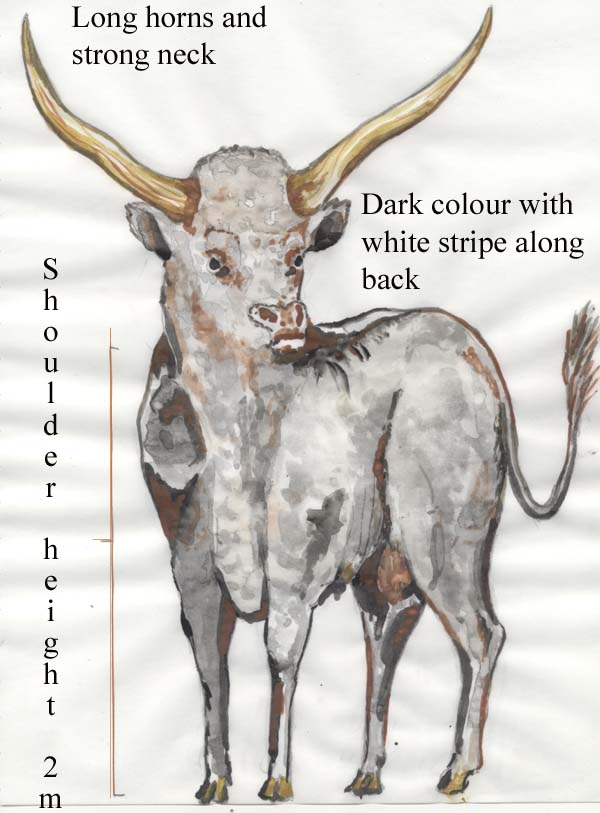

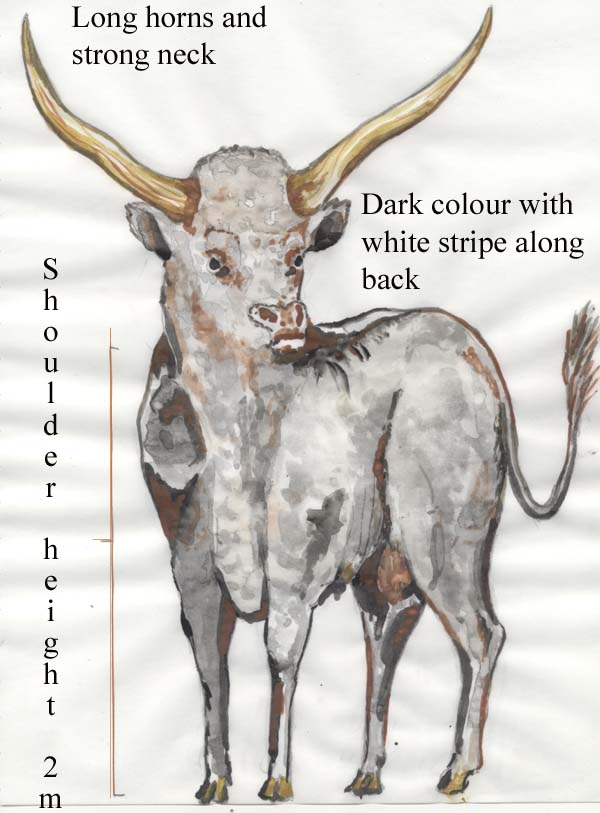

Sketch

of Bos primigenius - the

Aurochs (plural aurochsen) - a butcher's nightmare - vicious horns and

tough meat.

Migrations and mixing. In North America, cattle

were introduced by

Spanish settlers to the Southwest USA, giving rise to breeds such as

the Texas

Longhorn. But in the north, the cattle

were mainly derived from primitive breeds brought by French and British

settlers. Bos primigenius

genes were probably carried by the Spanish cattle while the primitive

northern

breeds were probably a mixture of B. primigenius and B.

longifrons. In early settlements,

the primary importance

of cattle was their ability to pull a plough or a cart, and they were

not

normally slaughtered until the end of their working life. Improved

British

breeds of cattle developed in the late 1700s and 1800s were imported

into North

America to form the basic Shorthorn, Angus, and Hereford stock. Between 1905 and 1920, Bos indicus

(Brahman cattle from India) was introduced into the southern USA for

its

heat tolerance. The most recent phase

of beef breed development in North America has been a re-introduction

of

Continental European beef breeds with rapid early growth and a large

mature

frame size - animals preserved as draft animals where steam engines

were

scarce. The large size of some of these breeds suggests they may

contain

genes derived from Bos primigenius. There is renewed

interest in

early maturing breeds, such as Angus, because of their ability to

produce

fine-grained, tender beef. Whether or

not these features will survive the current selection practices in

favour of

rapid early growth and a large mature frame remains to be seen.

Bison. The

bison (Bison bison), known as

the buffalo in American folklore, was nearly hunted to extinction but

now is

protected and ranched. Ranch bison is sold commercially. The

traditional prime

parts were the tongue and the hump, but steaks and burgers are now the

main

commodity. Bulls can reach a

massive size, around 1,000 kg live weight, but

commercial meat is from smaller animals.

After being on a finishing ration to a slaughter age of 14 to 15

months,

carcasses weigh around 276 and 248 kg for bulls and cows, respectively.

Dressing percentages (defined in LAB 1) are about 60%, but the

carcasses are light in the

hindquarter. Bison meat is dark, but this does not show after cooking.

Treating

bison carcasses like those of beef animals, cooler shrink losses are

slightly

higher than those for beef, probably because of the lighter fat cover

and

larger area of exposed muscles. However, shrink losses from bison

carcasses may

be improved by blast cooling. The saleable yield of meat trimmed to

retail

standards is around 78% of cold carcass weight. Shear values measuring

the toughness of the meat tend

to have a wider range than those of beef but may be generally improved

by

electrical stimulation (which prevents cold-shortening, defined in LEC

13). The ultimate pH (defined in LEC 12) of bison meat is within a

typical range

for red meat (say pH 5.4 to 5.7). The main marketing feature of bison

meat is

that it tends to have a lower fat content than beef.

Buffalo. African buffalo (Syncerus

caffer) come in several

sizes, ranging from the dwarf forest buffalo of

West and Central Africa to the

heavy Cape buffalo of South Africa. For bulls

and cows, respectively, carcass weights of 380 and 326 kg have been

recorded,

with dressing percentages up to about 50%.

Yak. The domesticated yak of China

and Mongolia is Poephagus (also known as Bos grunniens).

The wild yak

may be called Bos mutus. The domesticated yak of Asia is smaller

(maximum around 550 kg live weight for bulls and 350 kg for cows) than

the wild

yak. Yak hair is long and shaggy and is underlain by fine wool. The

tail is a

long brush, which is unusual for bovines. Yak meat is of secondary

importance.

Milk and hide products are more important.

2.2 Origins of pork

Species of pigs. Fossil pig skeletons have been

found in geological deposits dating back to the Pliocene period in

Europe and

Asia. Domestic pigs of Europe and North

America appear to be a mixture of two original species of wild pig: Sus

scrofa,

the wild boar of Europe found north of the Alps, and S. vittatus,

the wild pig now only found wild in the Malay Peninsula.

Wild pigs of the same genus (Sus) but

of different species to domestic pigs are found in India and Ceylon (S.

cristatus). The domestic pigs now

found in China are

usually considered to be S. vittatus.

Whether or not S. scrofa and S. vittatus

should be considered as separate species is a difficult question

because

transitional races are now widespread, thus demonstrating the obvious

point

that the hybrids are fertile. The

scientific distinction between S. scrofa and S.

vittatus

is based on the shape of the lacrimal bone in the skull (located round

the

orbit of the eye and supporting the tear duct from the eye to the nose). Several different subspecies of wild swine

are recognised: Sus scrofa scrofa, Europe; S.

s.

meridionalis, Mediterranean; S. s. barbarus,

North

Africa; S. s. attila, Eastern Asia; and S. s. palustris, found

in the archaeological excavations of Swiss Neolithic lake dwellings.

Early

evidence of

pork consumption. In the

bone heaps around the

eating areas of prehistoric peoples are found the remains of three

types of

pigs: bones of wild pigs obtained from hunting, bones of large pigs

probably

put out to forage, and bones of small pigs probably kept in confined or

covered

areas. Remains of domesticated pigs are

not found before Neolithic times (the agricultural revolution when man

became a

settled farmer) and, since pigs are difficult to control (they do not

easily

form herds like the ruminants), the nomadic farmers of earlier times

probably

did not have any pigs. Tribal conflict

between settled farmers and warlike nomads may explain why domestic

pigs, the

invention of the settled farmer, were first prohibited by some

religions. Another factor is the existence

of parasites

such as the pork tapeworm and trichinella (described in LAB 3).

Because of their

rooting

habits when foraging, pigs probably produced a dramatic change in the

local

ecology by reducing woodland undergrowth and allowing grass to grow. Before the invention of ploughing, pigs may

have been driven over seeded ground to embed the seeds.

Pigs may be used to hunt for underground

mushrooms (truffles) or to retrieve game, and these habits might have

been

important to primitive farmers.

Breeds of pigs

In medieval times, herded pigs

had a long snout and legs. Around the year 1800, Chinese pigs were

introduced

into Europe and combined with Sus scrofa.

This resulted in a dramatic phenotypic

change as pigs became thick-set in shape, smaller in size and laid down

fat

earlier in life.

Early development

of pig

breeds was influenced by factors such as ease of taming, socially

structured

behaviour, large numbers of offspring at relatively short intervals,

early

rapid growth and maturation, and longevity.

In the 1800s, the ability of pigs to store large amounts of fat

was

considered a desirable feature because, before the widespread use of

fossil

fuel energy for industrial machines, ordinary people expended large

amounts of

energy in their daily work. The high

caloric content of fat and the high fat content of pork once provided

important

food energy. Nowadays, however, there

is intensive selection against fatness and in favour of lean muscle

development. For the gourmet, however, nothing comes close to fat pork

from an

old-fashioned pig, especially if it is properly conditioned.

3.3 Origins of lamb

There are many

different wild

species and domestic breeds of sheep in five main groups;

(1), the moufflon

from Mediterranean countries;

(2), urial from southern

Russia;

(3), argali from

the Himalayas;

(4), bighorn from Canada and

eastern Russia; and

(5), domestic

sheep, Ovis aries.

Sheep

were domesticated at an early stage in the transition from nomad to

settled

farmer. Goats probably were domesticated before sheep, but the

domestication of

sheep precedes that of cattle and pigs.

Numerous characteristics have been changed by domestication. Many wild types of sheep have a wool-hair

mixture and, in hot climates, certain species are almost naked. Wool bearing sheep probably were derived

from animals originating in cold or mountain conditions. Domestic sheep

show a

range from very short to very long tails, but all wild types have short

tails. Some sheep deposit fat in their

tails. The lop-eared characteristic is not found in wild sheep and was

produced

very early during domestication. A convex nose is a striking feature of

many

breeds of sheep and is associated with a decrease in length of the

jaws, which

is a common feature in many other domesticated animals such as the pig

and

dog. Wild sheep often wield an array of

elaborately shaped horns. During

domestication the number has been reduced to a single pair, or horns

have been

lost altogether (polled). Animals kept in arid, rocky conditions derive

an

advantage from long legs, while smaller sheep are better for winter

housing in

colder climates.

3.4 Origin of chicken

The domestic

chicken is

descended from the Red Jungle Fowl, Gallus gallus.

Chicken is

used as a generic term in some countries whereas, in others, chickens

are

categorised by age and type. In France, for example, the age range is

from

young poussin to the poule, an old fowl. Similarly, in North America,

although

different breeds usually become anonymous after slaughter, a series of

carcass

types is defined by age and size.

Rock Cornish are 4 to 5 weeks of age, their

carcasses weigh less than about

0.8 kg, and they may be males or females.

Broilers or fryers are about 5 to 8 weeks of

age, have carcass weights

from

0.8 to

1.8 kg, and may be males or females.

Roasters are males or females older than 9 weeks with

carcasses over 1.8

kg.

Capons are castrated males over 9 weeks of age and with

carcasses over 1.8

kg. Surgical castration is difficult (because the male gonads

are inside the

body cavity near the kidneys, as described in LAB 4) and has been

replaced by hormonal castration in

most countries.

Chicken carcasses with tender

meat may be identified by their soft, pliable and smooth‑textured skin,

and by

their flexible sternal cartilage. Chickens such as roosters and mature

hens

producing relatively tough meat are identified by their greater age,

coarse

skin, and stiff sternal cartilage. Several features may be used as a

guide to

the age of a chicken. Young birds have unwrinkled combs with sharp

points. In

older birds, the comb becomes wrinkled with blunt points. The plumage

becomes

worn and faded in older birds, unless the birds have just moulted. With

age,

the subcutaneous fat becomes darker and lumped under the main feather

tracts,

and the pelvic bones become less pliable. Old chickens have large scales

which are rough and slightly raised and their oil sac becomes enlarged

and

hardened. Older male chickens develop long spurs.

3.4 Origin of ducks

Study hint. The

scientific names for the species of the wild ducks are for the hunters

and bird-watchers! No need to learn them.

Wild versus domestic ducks. Ducks,

geese and swans are grouped

together in the Order Anseriformes. Ducks comprise the Family Anatidae.

Ducks

are poor walkers but good swimmers, which means their legs are set far

back in

the body and are well muscled. Ducks are hunted extensively for their

meat. The

main types are the surface-feeding ducks such as the wild mallard (Anas

platyrhynchos),

teal and widgeon (Mareca americana);

the diving ducks such as the redhead (Aythya americana),

canvasback (Aythya valisineria) and ring-necked duck (Aythya

collaris); the sea ducks, which seldom provide meat with a

pleasant

taste; stiff-tailed ducks such as the ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis);

and the mergansers, whose meat is seldom palatable.

Thus, wild ducks produce meat with a wide range

from delectable to unpalatable. How much of the range is hereditary and

how

much is nutritional? Breed differences in the taste of poultry meat are

slight

to undetectable, so I would join most others in supposing that the

range in

palatability of duck meat is largely nutritional. Thus, the unpopular

taste of

meat from sea ducks and mergansers reflects what the ducks have been

feeding

on. At the other end of the range, the canvasback is rated very highly

for the

taste of its meat, but is instantly disqualified if it has been feeding

on

rotting salmon. Probably one of the key

features of this dietary effect relates to the digestion of fats and

oils in

the bird’s diet. Fats and oils are formed from triglyceride - three

fatty acids

bonded to a glycerol backbone like the three arms of a capital letter

E. As the

triglyceride is digested and moved around the body to be deposited in

the

duck’s own fat, nothing happens to the structure of the fatty acids, they just

get uncoupled and recoupled to a glycerol backbone. Thus, a fatty acid

with an

unpleasant taste from rotting salmon can move, unchanged, from the edge

of the

sea to the edge of your plate (details in LEC 19).

Two types of ducks

have been

domesticated and are extensively farmed, these are worth knowing.

The mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

and the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata). The Muscovy may be

identified by its claws (it is able to perch) and a red caruncle or

knob

between the beak and the eyes. Breast meat from female Muscovies may be

tougher, drier and stronger in taste than that from males. The main

changes

produced by domestication have been to increase growth rates and reduce

the

colouration of feathers. Carcass conformation is often not much

different from

a muscular wild duck. Apart from

numerous duck breeds of layers and ornamentals, there are many meat

breeds

around the world. The top ratings

might be the Aylesbury in

England; the Rouen,

Nantes and Barbary in France; and the Long Island in the USA. But this

would

probably be argued by fanciers of other breeds such as the Blue

Swedish,

Crested, Pekin, and Black Cayuga. The muscular Muscovy is the winner if

meat

yield and leanness are the main criteria.

In Canada, ducks

are separated

into a broiler-fryer category, less than 8 weeks of age, weighing 1.8

to 2.8

kg, either males or females; as distinct from the larger roaster, up to

16

weeks of age, either male or female. In Muscovies, the male is larger

than the

female. Youthfulness in ducks is detected by softness of the bill,

sternal

cartilage and trachea.

3.5 Origin of turkeys

History of the word - turkey.

Originally, an English

turkey-cock was a guinea fowl.

Guinea fowl had been

introduced from

Africa and were a paradigm of showiness, as in Shakespeare’s Twelfth

night,

“Contemplation makes a rare turkey-cock of him.” With the exploration

of North

America, the name was applied to the ancestors of the birds we now call

turkeys, Meleagris gallopavo.

The geographical range of

wild M.

gallopavo is from southern Canada, through the eastern and

southern USA,

down to Mexico. After the Spanish invasion of Mexico, Mexican strains

of M.

gallopavo were introduced into Europe where they were gradually

improved

and assumed the English name of turkey. Thus, when the English and

French

settled farther north in North America, turkeys (M. gallopavo)

were re-introduced as domestic birds which were smaller and more

compact than

their wild ancestors. Agricultural development then restricted the

range of

wild turkeys, although they are now successfully conserved in various

national

parks and protected areas. In the old

days, turkeys were eaten only on special occasions such as Christmas.

But

turkeys are now eaten every day, partly because of the invention of

numerous

processed turkey products, ranging from cooked breast meat slices to

turkey

sausage, and partly because customers have been introduced to a range

of

relatively small turkey cuts.

Further information

J. Clutton-Brock (1987). A Natural

History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge University Press, and

British Museum (Natural History). Very scholarly - but easy to

read.

L. Alderson. (1994). The Chance to

Survive. Pilkington Press, Yelvertoft, England.

Super pictures and compulsive reading for anyone who loves farm animals.

Trivia

Bos primigenius.

Water colour of my imaginary butcher's nightmare.

Syncerus caffer.

Water colour from the back of a truck in Kruger Park, South Africa.

Duck. Dendrocygna viduata

on a farm pond in Brazil (local name Marreca-Piadeira).

Melagris gallopavo,

Singhampton, Ontario.