LAB 3.4 Skinning & integument

PLAY VIDEO

The video shows how the pelt is removed, while the following text

describes the basic properties of the integument.

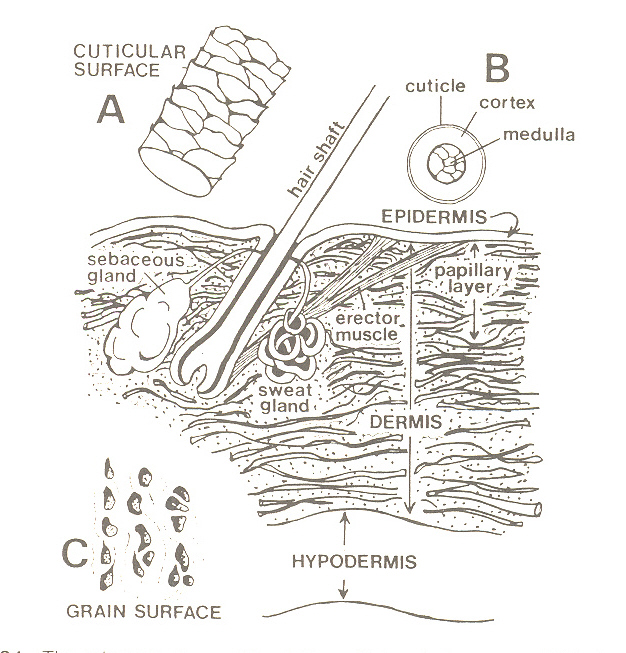

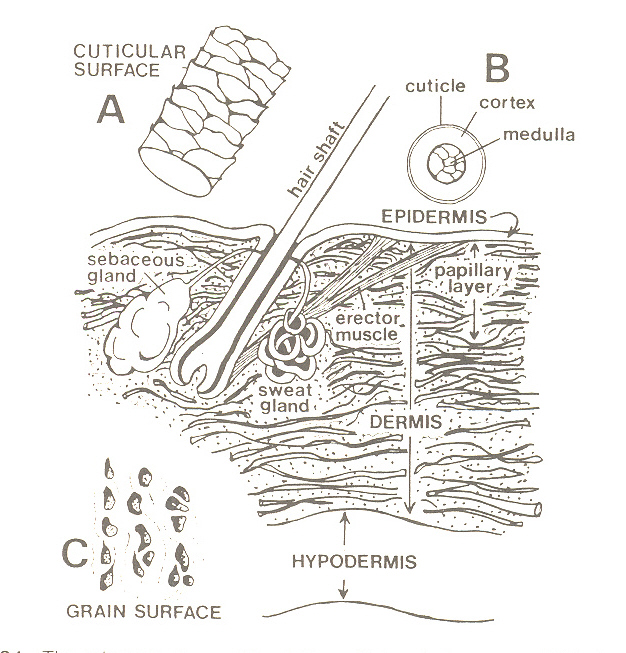

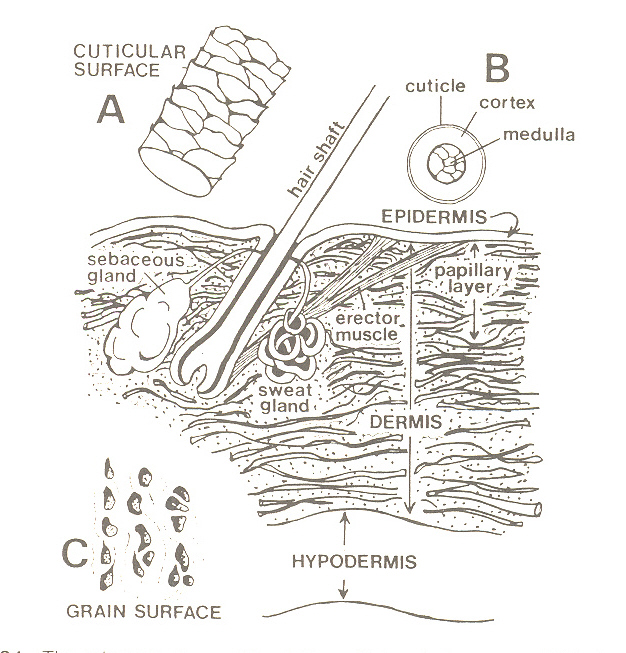

INTEGUMENT

Animal skin

is composed of three basic layers. From

outside to inside these layers may be called the (1) epidermis, (2) the

dermis,

and (3) the hypodermis. The epidermis is formed by layers of flat cells

composing a stratified squamous epithelium. New cells originate in the

lowest

layer and become keratinized as they are pushed to the surface. Keratin is a fibrous protein that also forms

the substance of hair, horns and hoofs.

At the ultrastructural level it is deposited in a fibrillar form

which

then may be incorporated into a granular form.

Hair follicles

Each hair

follicle develops from an inpushing of the epidermis down into the

dermis. Hair is formed by epithelial cells of a papilla at the base of

the follicle. There is considerable

variation in the rate of hair growth in meat animals.

For example, the average length of bovine hair may reach a

maximum between 6 and 24 months, and then may decrease. The

underlying sequence of events in hair growth is due to the periodic

shedding of

hairs from their follicles. The bulb at

the base of the hair eventually becomes hard and clublike.

This holds the hair in its follicle for some

time, but no further growth is possible. Eventually the hair is

released when a

new hair starts to form in the base of the follicle. This cycle

determines the

average external hair length and is influenced by factors such as

climate, age,

nutrition and breed. Chemical analysis of animal hairs may be used to

measure

the nutritional status of an animal, but the method is not very precise

.

Most

mammalian hairs and bristles have three layers that appear as

concentric rings

in a cross section through the hair shaft. From outside to inside

these are: (1) a thin cuticle, (2) the cortex, and (3) the large cells

of the

medulla. Many of the wavy wool fibers of a sheep's fleece lack a

medulla but,

like strong straight pig bristles, they are still composed of keratin.

The high

tensile strength and low solubility of keratin in hair and wool fibers

is

caused by the cross‑linking of protein chains by disulfide bonds,

hence,

dietary sulfur is important for wool production in sheep. In

sheep, the sebaceous glands that open into the wool follicles produce

an oily

secretion called lanolin. Pelt removal is more difficult for older

lambs than

for young lambs, and for ram relative to wether lambs,

but the reason is unclear and does does not appear to be related to

collagen

structure.

Sweat glands

In meat

animals, most of the sweat glands open near the entrance of hair

follicles.

Although less conspicuous than the sweat glands of human skin, they

still make

an important contribution to thermoregulation in meat animals. It has

been suggested that hair follicles exert some control over the

development of surrounding adipose tissue.

Feathers

Feathers are

also formed in follicles. The follicles

are grouped in feather tracts that are readily visible on the skin of

the

eviscerated carcass. In the spaces between the tracts, the follicles

produce

only filoplumes with a rudimentary feather vane at the end of a

hair‑like

shaft. The arrangement of feather follicles is governed by waves of

morphogenetic activity that move across the skin of the embryonic chick

like

ripples on a pond. The large feathers of the wings are called

remiges while those of the tail are called retrices. The contour

feathers provide

the main covering of the body and are interspersed with filoplumes.

Young birds

have large numbers of down feathers. The structure of the vane of a

typical

feather resembles a hollow quill that has been obliquely sliced and

unrolled. Thus, when it is formed within

the follicle

it is like a hollow cylinder. The lateral branches or barbs of the vane

are

held together by hooked anterior barbules that catch on the saw‑like

edges of

adjacent posterior barbules. The skin of poultry is dry and does not

produce

its own oil. In poultry, there is an oil gland located dorsally to the

stumpy

tail of the bird. The oil is distributed when the feathers are kept in

order as

the bird preens itself.

Melanocytes

Pigment

cells or melanocytes are located in the deepest layers of the epidermis

or in

the underlying dermis. Melanin is a pigment formed in organelles called

melanosomes. Melanin is passed from

melanocytes to skin cells by cytocrine secretion. Melanin is formed

from the

oxidation of tyrosine by tyrosinase. Absence of this enzyme results in

an

albino animal. Variation in the color of farm animals is caused by

variations

in the amount and distribution of melanin. Melanin may be extracted

with an

aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide and then recovered by

acidification. Melanin

is a polymer based on indole monomers, but there is also a protein

component

involved that makes precise determination of its structure difficult. The distribution of melanin

over the animals' skin is determined prenatally by an interaction

between the

migration patterns of melanocytes and the diffusion patterns of the

messenger

substances that either activate or suppress the synthesis of melanin. A

single dominant gene determines the belt pattern marking that runs

over the shoulders and forelimbs of some breeds of pigs.

Leather

The

epidermis is supported on the ridged surface of the underlying dermis.

The

upper region of the dermis, often called the papillary layer of the

dermis, is

a tightly woven network of collagen fibers with some elastin fibers.

After the

tanning of a hide to make leather, the papillary layer becomes the top

surface

of the leather. With a hand lens, the

openings where the hair follicles once penetrated the dermis are easily

visible). When the leather is turned over, the much looser coarse

fibrous weave of the lower dermis is evident.

In pigskin, the follicles of the strong bristles are rooted at

the

lowest level of the dermis so that many of the follicles almost

perforate the

leather.

When the

hide is removed from the carcass, the separation is made through the

deepest

layer of the integument ‑ the hypodermis.

Fat is often deposited in the hypodermis and, particularly in

sheep, may

even infiltrate the dermis. Numerous blood vessels run through the

hypodermis

to reach the extensive vascular bed (for heat dissipation) in the

dermis. The

hide weight of a typical lean steer is about 7% of the live weight, but

there

is considerable seasonal variation (Dowling, 1964) with colder climates

inducing heavier hides and there are also differences between types of

cattle.

Bos indicus cattle have relatively heavy hides while Holstein cattle

have

relatively light hides.

Beef hides

are graded on their cleanliness and degree of damage due to branding or

warble

fly larvae. If beef hides have been processed with a high standard of

hygiene,

the collagen of the inner layer of the hide may be used for processed

food

products such as sausage casings. Green hides (those from recently

slaughtered

animals) are treated with sodium chloride prior to tanning. The hides

are

trimmed, split into left and right sides, and soaked for several days

in water. Then the hides are dehaired in a

calcium

hydroxide solution that contains sodium or calcium hydrosulfide. The

conversion

of a hide to leather occurs when it is TANNED, originally with a tree

bark

extract but now usually with sodium dichromate. Hair remnants are

physically

forced from the hair follicles (scudding) prior to deliming in sulfuric

acid.

Elastin fibers are removed enzymatically before the hides are pickled

in sodium

chloride acidified with sulfuric acid.