Gordon King, Animal Science, University of Guelph

The early humans first domesticated animals as a convenient means of meeting immediate needs for food clothing and transport. Subsequently, for many thousands of years, livestock remained only one component of a regionally self-sufficient and basically sustainable method to satisfy human demands. Even within our own region, subsistence agriculture persisted until near the end of the nineteenth century. The early pioneers brought sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, poultry and horses to Upper Canada, with livestock numbers usually exceeding people in the initial settlement stages. Homesteads increased quickly in numbers and prosperity but Ontario remained a collection of mixed farms well into the current century. The predominant pattern until after the first world war consisted of family units loosely organized into self-contained rural communities providing food for a number of small but growing urban centers. Subsequently, mechanization and technological innovation produced substantial challenge, transition, change, reduction and uncertainty. Most surviving farms are now highly specialized, labor efficient, capital intensive and management demanding components of an integrated agri-food industry producing for both a regional and global market.

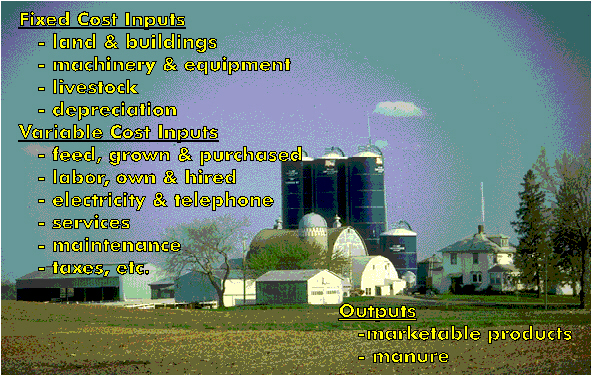

Farm animals function to collect and to concentrate energy in the form of feed nutrients and to process or convert these into consumsables, convertibles or other products humans need or want. Successful operation of a modern farm demands sound planning and astute decision making throughout all stages of the production sequence. The decision making process might go as follows:

A considerable number of farmers throughout the more developed regions of the world have decided to operate livestock units that are:

The accompanying figure illustrates a typical livestock production sequence showing some of the general management choices affecting the entire operation and a number of decisions that must be made at specific stages.

Livestock contributions to human needs and wants were considered in a previous section of this course. Recall that in addition to their many beneficial attributes in resource conservation, domesticated animals provide convertible materials for clothing and other uses, plus draft power, a very important function in many regions. Perhaps their most universal and recognized bequest is consumable products for human consumption.

| Cereals | ||

| Roots, tubers & pulses | ||

| Nuts & oils | ||

| Vegetables & fruits | ||

| Sugar | ||

| Animal Products |

Modified from Taylor & Bogart (1988) Scientific Farm Animal Production. MacMillan

Commodities from domesticated animals can be divided broadly into two

general classes: those obtained from living animals and those only procurable

after slaughter. Products available before slaughter would include milk, eggs

and honey. Throughout most of human history these, like all livestock products,

were only available during very limited seasons of the year. However,

innovative production-management practices altered this situation so almost any

dairy or poultry item can now be found for sale year round in almost all

countries. In contrast to the situation for eggs and dairy products which are

obtained without slaughter, animals must be killed before their muscles can be

converted into meat. Until recent times meat was an infrequently enjoyed luxury

item for most societies. Modern techniques increased efficiency and reduced

cost of production which, combined with the increased affluence in many

countries, means that more and more people can now afford to purchase meat,

eggs or dairy products. This certainly increases demand for consumable products

from livestock and opportunities for those who supply them.

Successful farmers in the humid or subhumid

tropics manage pastures to insure that natural grazing is available for most of

the year. Those in most temperate climates must conserve forage and other feed

ingredients produced during the active growing season for use during late fall,

winter and early spring. Similarly, people in semi-arid regions who own

livestock must arrange alternative feeding for the dry season.

Successful farmers in the humid or subhumid

tropics manage pastures to insure that natural grazing is available for most of

the year. Those in most temperate climates must conserve forage and other feed

ingredients produced during the active growing season for use during late fall,

winter and early spring. Similarly, people in semi-arid regions who own

livestock must arrange alternative feeding for the dry season.

The productivity obtained from any animal depends on its genetics, which dictate the inherent potential to produce, plus the environment, which governs how much of the potential can be realized. Genotype by environmental interactions are often considered but this is perhaps an oversimplification of the actual situation in livestock production systems. Neither animals nor animal attendants are created equal and the latter can manipulate both the animal's genotype and its environment. Some attendants, through instinct, experience, training or a combination of these are more capable of providing care and conditions that satisfy the basic requirements needed for their animals to perform properly. Others, with little regard for animal welfare or appreciation of fundamental needs, fail to provide even the minimum requirements necessary for comfort, health or productivity. Thus, livestock production involves a complex interaction between genotype, environment and management. The genetic component dictates the potential to produce, the environment governs how much of the potential can be realized, and management decisions influence both of these factors.

If animals have the genotype for high production and all of the necessary inputs are available, a competent manager should be able to provide an environment that allows livestock to reproduce efficiently and to express much of their inherent genetic potential. Whether this is profitable depends on the total cost of all inputs and how these relate to the value of product produced. The science of animal production has advanced to the state where knowledge exists on how to improve many of the components involved with reproductive performance. Unfortunately, for some of these procedures the cost associated with providing the required inputs may exceed market value of the additional offspring or commodity produced. Each technology must be critically evaluated to determine whether it should be cost effective when used on commercial farms before any widespread introduction is promoted.

Sound management procedures carried out by competent animal attendants should minimize problems. Murphy's Law, however, applies in all animal units. A very important consideration in any type of livestock production is what to do whenever things do not go as expected. Inputs, procedures and outputs should be evaluated and compared to targets at frequent intervals to provide a close watch on what is happening. Occasionally, such monitoring might indicate less than optimum performance that could be attributed directly to some reasonably obvious pathological condition. Unfortunately, in most instances, the cause will not be obvious. Thus, it is necessary to analyze and summarize past records to see what has been happening over time, to asses the environment to understand conditions under which the animals must exist, to evaluate the husbandry to see how the stock is cared for, and to conduct a clinical examination to evaluate the current health status. A thorough investigation of each aspect provides a sound basis for problem identification.

Farmers, veterinarians and consultants providing service to the livestock industry must work towards identifying and correcting the actual cause of any problem, rather than simply treating the symptoms.

Perhaps the most pressing challenges currently facing the livestock

industry in Ontario, in Canada and throughout the rest of the world are:

i) adapting to the continual technological innovations and associated pressures

to optimize input/output ratios for economic returns;

ii) to accomplish this while developing environmentally friendly methods that

provide long-term sustainability.

Major concerns for many regions are:

1. Competitive Ability:

2. Consumer Preferences:

3. Inflexibility:

The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) provides considerable general and management related information about the livestock industries in central Canada. This material can be accessed through the OMAFRA Livestock Index Page.

Go to Dairy Production - Background and Planning

Go to Dairy Production - Housing, Feeding, Health and

Reproduction

Go to Beef Production

Go to Pork Production